Once, decades ago, honeypots were synonymous with deception techniques in the cyber world. These clever pieces of data or desirable information were used to lure attackers and influence, often in real time, their behavior.

Honeypots were sacrificial dumb computers, or simple emulations of dumb computers, used to gather basic information about an attack. They opened the door to gathering attack data and telemetry, and inspired a generation of cyber defense pioneers. However, the initial enthusiasm for honeypots soon faded when it became obvious that maintaining a credible illusion capable of harvesting telemetry data from real threats was no easy task. In fact, security teams could barely manage and patch their main systems, not to mention worrying about ancillary “fake” systems that also needed care and attention. Honeypots became a tool rarely used outside academia. (If your house is on fire, you aren’t going to have time to create a fake house next door to see if the arsonist strikes there first. You are going to put out the fire.)

Today, honeypots have evolved, and they still remain an important tool in the deception technology kit. However, deception technology has moved beyond the mere honeypot, and now has features that allow it to appear more credible, exfiltrate key data, and perform telemetry, and no longer in the tedious, manual manner of earlier honeypots.

The fact is, however, that deception technology is still in its youth. Many high-level security professionals still mistakenly believe it’s nothing more than a collection of honeypots. Mere numbers disprove this theory, as, the global market for deception technology is projected to reach a staggering $4.6 billion by the year 20271. While it is true that both honeypots and deception are meant to trap, trick and mislead threat actors, the two concepts have some major differences.

What Exactly is a Honeypot?

A honeypot is, by definition, “a computer security mechanism set to detect, deflect, or, in some manner, counteract attempts at unauthorized use of information systems”2. A honeypot should be enticing, as they are specially designed to attract adversaries.

Speaking in more concrete terms, a honeypot can be anything from data and information to services or some other resource. The name itself clues us into the goal: to attract flies, aka undesired invaders, and trap them in a way that allows us to observe them and even halt their movement.

Honeypots are most often designed to mimic likely targets of cyberattacks. This computer system or tool is created to fool attackers into thinking it is a legitimate system. If a honeypot is well designed and maintained, eventually it will attract attackers. When an attacker takes the bait, the honeypot is used to gather information and notify the owners of the honeypot of attempts to access, which sets other security protocols in motion.

Honeypots are super important tools when designing a smart defense against attackers.

Types of Honeypots

So, what kind of different honeypots are there? Honeypots are generally categorized in two different ways3.

The first is by the purpose for which they are built. Under this categorization, honeypots are known as one of two types:

- Research honeypot – These are used to gather general intelligence that can later be analyzed and put to various uses. They are quite complex and used mostly by academia or governments who are able to process loads of data and TTPs.

- Production honeypot – These are generally simpler, as their main goal is to protect a network. They are used within an organization as a form of protection.

The second way to classify honeypots is by the level of interaction or complexity they have. Under this categorization, there are generally thought to be two divisions:

- Low-interaction honeypot – honeypots that imitate services and systems that are known to attract attackers. Useful for collecting data from blind attacks.

- High-interaction honeypot – honeypots that behave like an actual production system. The attacker can roam as they would in true production infrastructure, meaning a multitude of insights can be gained by studying the TTPs left behind. Difficult to detect but expensive to build and maintain.

The History of Deception: From Honeypots to Active Defense

You can learn a lot about why deception is not just honeypots by looking at the history and evolution of the honeypot.

— 1989 —

The Cuckoo’s Egg

One of the first examples of honeypots in popular culture actually predates the terminology itself. The Cuckoo’s Egg is a nonfiction account of Clifford Stoll’s hunt for a hacker when he worked at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. A 75-cent accounting discrepancy led him to an obsession with an unidentified intruder on the network, so he created a series of elaborate hoaxes to attract and trap the hacker. These traps are what are now known as honeypots, and it was the first time this type of activity was logged and documented. Stoll saw the hacker pay special attention to an SDI identity he created, and filled the network with large files of impressive-looking documents to sweeten the deal.

— 1998 —

Deception Toolkit

The launch of the Deception Toolkit marked an important phase in the evolution of honeypots. The page, designed by Fred Cohen, is still online today, and was one of the first build-your-own honeypot tools. Commonly known as DTK, this collection of PERL scripts emulated various known vulnerabilities, such as an old Sendmail vulnerability that gives out a fake password, which entices attackers down a rabbit hole of cracking passwords that are not real.

— 1999 —

The Honeynet Project

The concept of several honeypots on a network is known as a honeynet, and is useful for monitoring larger networks that need more than one honeypot. Lance Spitzner, founder of the Honeynet Project, published a paper in 1999 called “To Build a Honeypot”. This grew into a community-driven, non-profit organization dedicated to sharing information about cybersecurity in general and honeypots in particular.

One of the main goals of the Honeynet Project is to learn about unknown vulnerabilities. This organization’s work differed from the Deception Toolkit in that its goal was not just to collect data on what is already known, but to learn about unknown vulnerabilities.

— 2003 —

Global Reach

The Honeynet Project flourished, uniting security figures passionate about open source defense. It didn’t take long for the movement to go global. In fact, CounterCraft’s CEO, David Barroso, started the Spanish chapter of the project in 2003. He and his colleagues translated many of the documents and tools into Spanish… and the website is still live!

— 2007 —

The Next Generation

Low-interaction honeypots were the next step in the evolution. Honeyd, whose stable version launched in 2007, is an open source computer program created by Niels Provos that allowed virtual hosts to be configured to mimic several different types of servers, allowing the user to simulate an almost infinite number of computer network configurations.

At this time, honeypots were deployed mostly to get an idea of what was happening on different networks. The technology was, for the most part, still too academic to translate to business. However, it got people looking at the idea of deception, and they could see that something was happening there.

— 2013-2015 —

A Budding Market

In the ‘10s, companies begin to build specific distributed deception products. Companies already in the space began to make distributed emulated honeypots. A few of them used distributed breadcrumbs.

Around this time, David Barroso, Fernando Braquehais and Dan Brett had some opinions on how to better the use of deception tools to create a more believable environment that could be deployed at scale and result in an effective active defense strategy. They formed CounterCraft to take advantage of the advances in the available tools, building more complex and robust systems.

The latest deception technology is truly avant-garde. A combination of distributed high-interaction honeypots, distributed breadcrumbs, and strategy, the next level of deception allows users of CounterCraft to manipulate a deception environment based on real-time threat intelligence gathered in order to influence an attack before it even happens.

Deception has come such a long way from where it was in the days of honeypots.

The Deception Technology Triangle

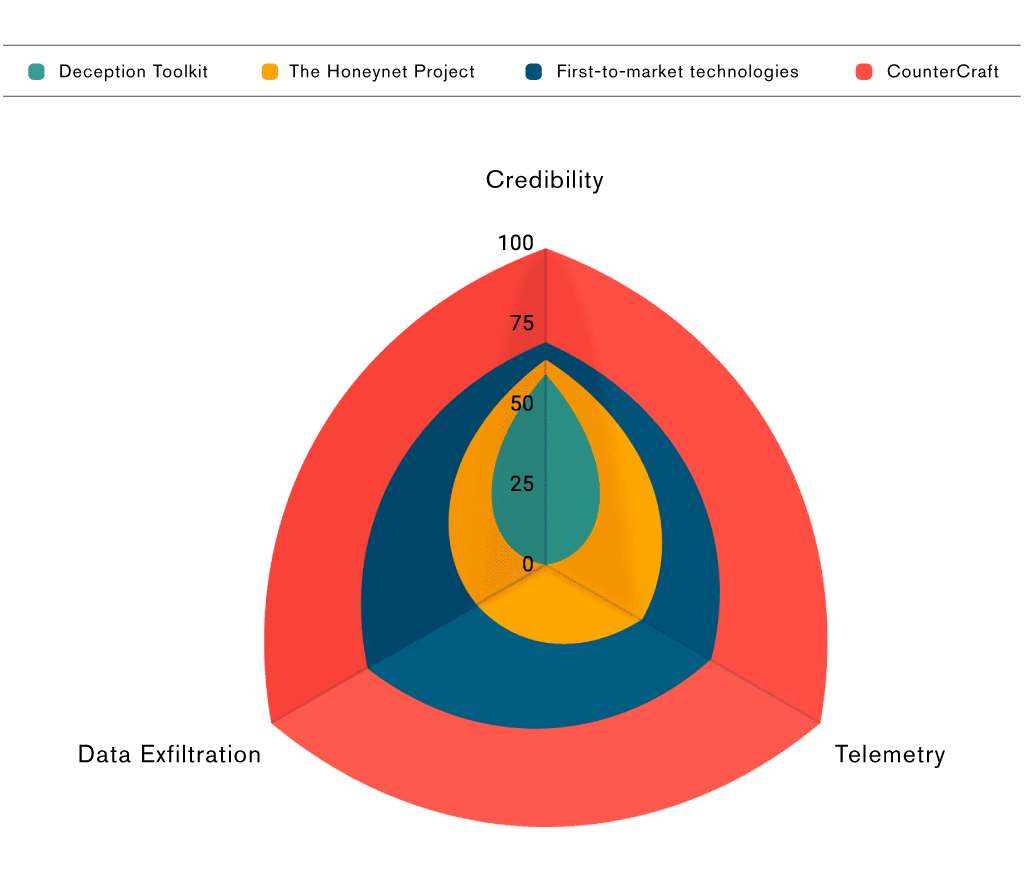

To work, deception technology must fulfill certain factors. Here at CounterCraft, we think of these three pillars as the deception technology triangle, a theory developed by Rich Munslow, CTO at the National Cyber Deception Lab.

The three pillars necessary for effective deception technology are:

- Credibility: Is it believable?

- Instrumentation / Telemetry: Are you able to gather deep data about what people are doing on the system?

- Data Exfiltration: Are you able to bring that data home without revealing yourself, so you can do something about it?

Previously, when deception technology was limited to honeypots, it could not fulfill the three pillars necessary to effectively detect, prevent, and manage attacks.

Deception toolkit

Deception Toolkit was not believable, and the instrumentation was poor. You had to visit the computer every six months and see whether it had any data on it, making data exfiltration tough.

The honeynet project

The Honeynet Project’s solution was still difficult and patchy, although it represented a slight improvement over the Deception Toolkit, as you could use the internet to retrieve the data collected.

First-to-market technologies

First-to-market technologies solved the data gathering issue, but they still have important credibility issues, making them not ideal for complex systems and high-stake networks.

CounterCraft

CounterCraft has solved deception. The CounterCraft Cyber Deception Platform has real IT and ActiveBehavior technology, a revolutionary way to keep honeypots and breadcrumbs from going stale. We have solved the deep data problem, thanks to a kernel-level implant that observes the actions of the adversary, which is stealthed to avoid detection. And, to top it off, we have a very well-engineered command and control infrastructure, ActiveLink, for bringing the data home in a secure and stealth way, meaning we do not give away the data to an adversary.

Far Beyond Honeypots: The Future of Deception Technology

The future of deception lies in a fourth axis on the deception triangle: the dynamic response. The deception triangle becomes three dimensional, as dynamic response capabilities allow you to shift and manipulate the environment to extract more information from your adversaries than they would normally leave.

This is something a honeypot could never do.

This is the CounterCraft difference

Competitors solve other areas of the deception triangle, they deploy at scale, or they gather deep data, but none covers the entire triangle, like CounterCraft. And, no one offers the possibility of entering into the fourth dimension: dynamically shaping the deception environment to elicit changes in behavior and better threat intel gathering.

Here at CounterCraft, we deploy some of the world’s most convincing and strategically sound deception environments, which is why we have worked with everyone from the U.S. DoD to NATO. Our deception platform and cloud services create environments that look ultra realistic.

A well-designed piece of deception technology should be realistic, interactive and tempting to the threat actor. This will enable those employing it to gain valuable threat intelligence. It should include human mistakes and replicate human behavior. CounterCraft’s offering is designed to find more active intrusion, and then to convince the attackers to reveal all the tools they have before they realize they are in a virtual decoy.

This is the future of deception technology.

Source:

1Deception Technology – Global Market Trajectory & Analytics, September 2020

2https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honeypot_(computing)